Heinrich Zille

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (March 2025) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

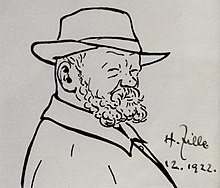

Heinrich Zille | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait 1922 | |

| Born | Rudolf Heinrich Zille 10 January 1858 |

| Died | 9 August 1929 (aged 71) |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation(s) | illustrator, caricaturist, lithographer, and photographer |

Rudolf Heinrich Zille (10 January 1858 – 9 August 1929) was a German illustrator, caricaturist, lithographer, and photographer, best known for his empathetic and satirical depictions of Berlin's working-class life.

Childhood and education

[edit]

Zille was born in Radeburg near Dresden, the son of watchmaker Johann Traugott Zill (known as Zille since 1854) and Ernestine Louise (née Heinitz), the daughter of a miner from the Ore Mountains. Originally a blacksmith, Zille's father later became a watchmaker, goldsmith, and inventor of tools due to his technical skill. Zille spent his early years in Potschappel, a suburb of the town of Freital in the Sächsische Schweiz-Osterzgebirge district, located approximately 8 km (5 mi) southwest of Dresden. However, his childhood was marked by significant hardship. His father was incarcerated multiple times in debtors' prison, and creditors frequently harassed the family, often forcing the young Zille to live with his grandmother. In 1867, the family moved to Berlin due to their mounting debts. While still in school, Zille began taking drawing lessons with the encouragement of a supportive teacher, who later advised him to pursue a career as a lithographer. Zille's father, however, wanted him to become a butcher—a profession Zille rejected, as he could not tolerate the sight of blood. Upon finishing school in 1872, he began an apprenticeship as a lithographer under the draughtsman Fritz Hecht on Jakobstraße in Berlin-Kreuzberg.

Life and work

[edit]

Military service

[edit]

From 1880 to 1882, Zille completed his military service as a grenadier with the Leib-Grenadier-Regiment, First Brandenburg Regiment No. 8, in Frankfurt (Oder) and as a guard at the Sonnenburg prison (now Słońsk in Poland). For Zille, these years were an unpleasant experience, which he documented in numerous notes and sketches during his free time. In one instance, he wrote: "We were assigned to the companies, entered the barracks, and the bedbugs were already lying in wait. In the beds, there was decaying rubbish, chaff as straw. Bad food. In return, we were daily smeared by the officers with a cesspool of barracks-yard witticisms and jokes. [...] It was part of troop training for such a fop of a lieutenant to be allowed on Sunday mornings, during locker inspections, to point at the picture of my beloved affixed to the inside of the door and ask mockingly: 'Your sow?'"

During his two years of service, Zille created episodic soldier sketches, mostly with a humorous tone; however, many of these works have been lost. He later processed his own military experiences in his "anecdotal soldier and war illustrations," which were published during the First World War in 1915 and 1916 as a series under the titles Vadding in Frankreich I u. II (Father in France I and II) and Vadding in Ost und West III (Father in East and West III).[1] These satirical yet predominantly patriotic booklets were widely regarded as glorifying war. Consequently, at the suggestion of his friend Otto Nagel, Zille produced more poignant anti-war illustrations titled Kriegsmarmelade (War Marmalade), although these were published long after the war in small editions and by then had lost much of their relevance.

Family

[edit]In 1883, Zille married Hulda Frieske, and the couple had three children together. Hulda passed away in 1919. Despite his personal loss, Zille continued to dedicate himself to his art, using his work to shed light on the struggles and resilience of Berlin's working-class communities.

Secession and success as an artist

[edit]Zille became best known for his often humorous drawings, which captured the defining characteristics of people, particularly 'stereotypes', predominantly from Berlin. Many of these works were published in the German weekly satirical newspaper Simplicissimus. He was the first artist to vividly depict the desperate social conditions of the Berlin Mietskaserne (literally 'tenement barracks')—overcrowded buildings where up to a dozen people might share a single room. These spaces housed individuals who had fled rural areas during the Gründerzeit, seeking opportunities in the rapidly expanding industrial metropolis, only to encounter even deeper poverty within the burgeoning proletarian class.[2]

Possessing an extraordinary talent for depicting the harsh realities of urban life with caustic humour and profound humanity. His works illustrated the struggles of society's most marginalised, including disabled beggars, tuberculosis-afflicted prostitutes, and poorly paid labourers, as well as their children. Zille’s art highlighted their resilience and unyielding determination to find moments of joy and dignity amidst hardship. By blending satire with compassion, he brought attention to the grim living conditions of Berlin’s working classes, particularly those residing in overcrowded tenements, offering a poignant critique of the social challenges of his era.

Despite his achievements, Zille did not regard himself as a true artist, often stating that his work was the product of hard labour rather than innate talent. Despite this, he was championed by Max Liebermann, who invited him to join the Berlin Secession in 1903. Liebermann prominently featured Zille's work in exhibitions, encouraged him to sell his drawings, and provided significant support during a critical juncture in Zille's life. When Zille lost his job as a lithographer in 1910, Liebermann urged him to pursue a livelihood solely through his art.

The Berlin 'common people' held him in the highest regard, and his fame reached its zenith late in life during the Roaring Twenties, a period marked by both widespread poverty and a flourishing of artistic expression. In 1921, the National Gallery acquired some of his drawings, and in 1924, the Academy of the Arts recognised his contributions by bestowing upon him a professorship. In 1925, Gerhard Lamprecht directed the film Die Verrufenen (Slums of Berlin), inspired by Zille's cartoon characters and stories. His 70th birthday in 1928 was celebrated across Berlin, marking a climactic tribute to his enduring impact. He passed away the following year and was laid to rest at the Stahnsdorf South-Western Cemetery near Berlin.

Photographer, Atelier August Heer, circa 1900

[edit]Between 1882 and 1906, Zille temporarily turned his attention to photography. The claim that he engaged in photographic work outside his workplace first appeared in 1967 in Friedrich Luft's book Mein Photo-Milljöh. 100x Alt-Berlin aufgenommen von Heinrich Zille selber (My Photo Milieu: 100 Pictures of Old Berlin Taken by Heinrich Zille Himself). In Zille's apartment on Sophie-Charlotten-Straße 88, a chest of drawers was discovered containing "418 glass negatives, several glass positives, and over 100 photographs, for which no negatives could be located." These images were known within Zille's family and some had already been published.

The photographs do not depict the refined imperial side of Berlin but instead focus on the everyday lives of Berliners in backyards or at funfairs. However, it remains uncertain whether Zille was the creator of these works. Doubts arise particularly from Zille's reluctance as a lithographer to use technical devices for creating images. Furthermore, no camera was found among his possessions after his death. Nonetheless, it is a fact that Zille worked as a lithographer for 30 years (until 1907) at the Photographische Gesellschaft in Berlin, where he also operated within the photographic laboratory.

Whether Zille himself took photographs remains a subject of debate. It has been suggested that he utilised the studios (ateliers) of August Gaul and Jakob August Heer to produce the nude photographs attributed to him from 1900–1903. These images document scenes within the studios, including models and artists at work. Of note is the fact that during this period, the animal sculptor August Gaul is verifiably documented as a photographer, with Zille serving as his developer in the photographic laboratory. Zille is believed to have regarded the camera as a "photographic notepad" for his graphic studies, drawing inspiration from various sources, including postcard motifs and press photographs.

Legacy and honours

[edit]Heinrich Zille Park, located on Bergstraße in Berlin's Mitte borough, was named in his honour by the City of Berlin in 1948. The park formerly featured a statue of Zille created in the workshop of Paul Kentsch; however, the statue's whereabouts are currently unknown, and the park has since been transformed into a children's adventure playground. A Zille Memorial statue, designed by Heinrich Drake in 1964–65, is located in the Lapidary within Köllnischer Park, also in Berlin Mitte. Additionally, an elementary school in Berlin's Friedrichshain district bears his name.

In 2002, a museum dedicated to Zille's work was opened in Berlin's Nikolaiviertel, in Berlin Mitte.[3] In 2007, a statue of him sculpted by Thorsten Stegmann was erected nearby.

Zille's artistic oeuvre also includes many erotic illustrations, some of which border on pornography while simultaneously portraying the lives of ordinary people. A selection of these works is displayed in the Beate Uhse Erotic Museum in Berlin.

In 1983, the East German director Werner W. Wallroth released a film titled Zille und Ick (Zille and Me, in Berlin dialect), based on a musical by Dieter Wardetzky and Peter Rabenalt.[4] While not a traditional biopic, the film incorporates elements of Zille's life into its narrative.

A drawing by Zille appears on a 55 Euro-Cent German postage stamp, captioned "Heinrich Zille, 1858–1929".

The South African politician Helen Zille is not Zille's grandniece. In her autobiography published in 2016, she retracted earlier claims suggesting such a relationship. Berlin-based genealogist Martina Rohde had previously documented that Heinrich Zille's handwritten records included a mix-up involving individuals with the same name but differing places and dates of birth.

Gallery

[edit]-

Zille Memorial in Köllnischer Park, Berlin, by Heinrich Drake

-

Monument to Zille by Thorsten Stegmann in the Nikolaiviertel

-

"As the outdoor public swimming pool appeared" (1919), by Zille

-

"School", by Zille

-

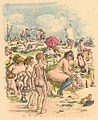

"Beach life in Berlin" (1901), by Zille

-

Modellpause (Model break), by Zille, circa 1925 'With artists, you first have to learn to understand what they say. If they want someone nude, they say: "Akt" ([nude] act); if they paint the breasts, they say "Büste" (bust); and if they want the back, where it's nice, they say "Kiste" (box).'

Selected filmography

[edit]- Slums of Berlin (1925)

- The Ones Down There (1926)

- Big City Children (1929)

- Mother Krause's Journey to Happiness (1929)

References

[edit]- ^ a b Zille, Heinrich (1916). Frankreich nach Russland, Vadding in Ost und West [France to Russia, Father in East and West] (in German). Berlin: Verlag der Lustigen Blätter.

- ^ "Heinrich Zille - Lambiek Comiclopedia".

- ^ "Zille Museum". Museumsportal Berlin. museumsportal-berlin.de/en/. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ "Zille und ick (1983)". IMDb. 1 May 2009. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

Further reading

[edit]- "From Zola’sMilieu to Zille's Milljöh: Berlin and the Visual Practices of Naturalism." Excavatio XIII. September 2000. 149–166.

External links

[edit]- Available Works & Biography Galerie Ludorff, Düsseldorf, Germany

- Documents from the life of the Zille family

- Newspaper clippings about Heinrich Zille in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

![Modellpause (Model break), by Zille, circa 1925 'With artists, you first have to learn to understand what they say. If they want someone nude, they say: "Akt" ([nude] act); if they paint the breasts, they say "Büste" (bust); and if they want the back, where it's nice, they say "Kiste" (box).'](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e1/Heinrich_Zille_Modellpause.jpg/120px-Heinrich_Zille_Modellpause.jpg)